-

![Michael Rosen]()

-

Investment Insights are written by Angeles' CIO Michael Rosen

Michael has more than 30 years experience as an institutional portfolio manager, investment strategist, trader and academic.

TALKIN' TURKEY

Published: 08-14-2018

The expression comes from Colonial America, but its exact origins are unclear, and its meaning seems to have changed over the years. Originally it was a phrase that denoted pleasant, or even silly, conversation. Today, “talk turkey” means plain, direct speech. Just the facts (ma’am). So, let’s talk turkey.

Turkey is a mess, on many levels, and it’s all self-inflicted. It is classic economic mismanagement for narrow political purposes, a pattern we’ve seen (literally) hundreds of times. Its symptoms are predictable, its cure is obvious, but the prognosis is bleak. Politics and personality are turning a manageable economic crisis into a catastrophe. Let’s briefly look at the symptoms before turning to the root causes.

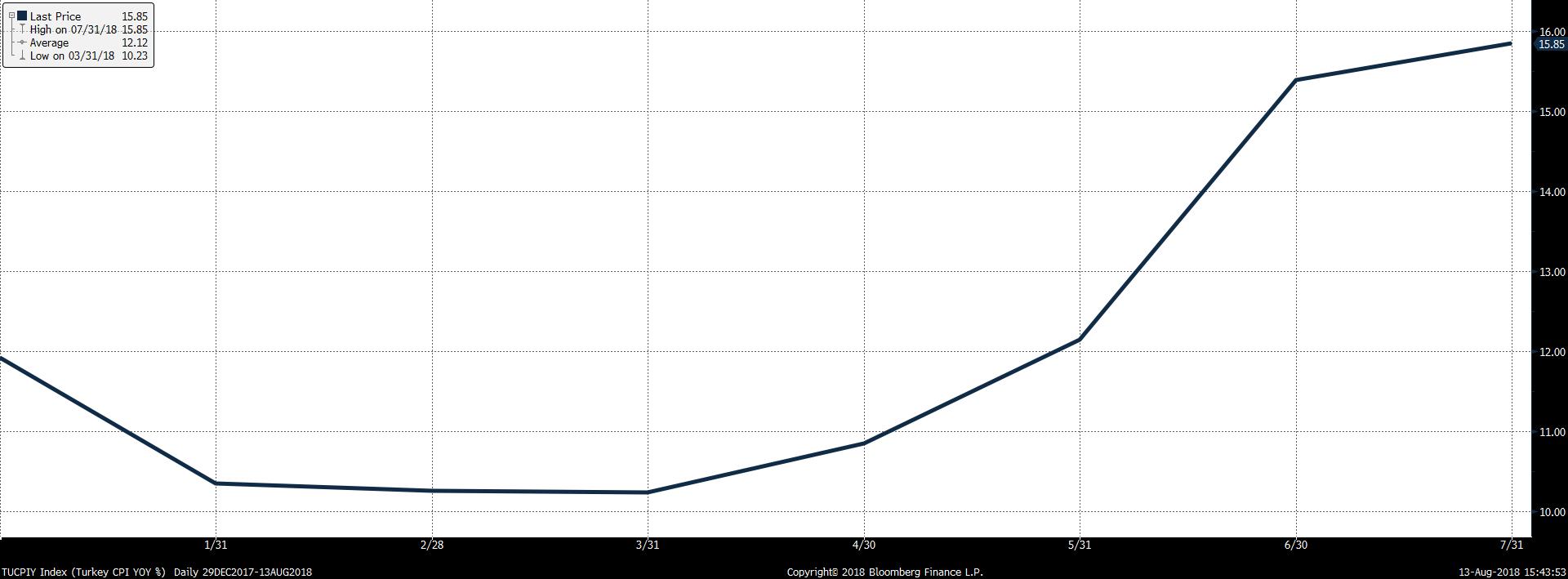

Inflation in Turkey has jumped to over 15% this year, and continues to rise (see first Chart). The lira (its currency), is down about 50% this year, 30% in just the past month (second Chart).

Turkey Inflation, YTD 2018

Turkish Lira per US Dollar, July-August 2018

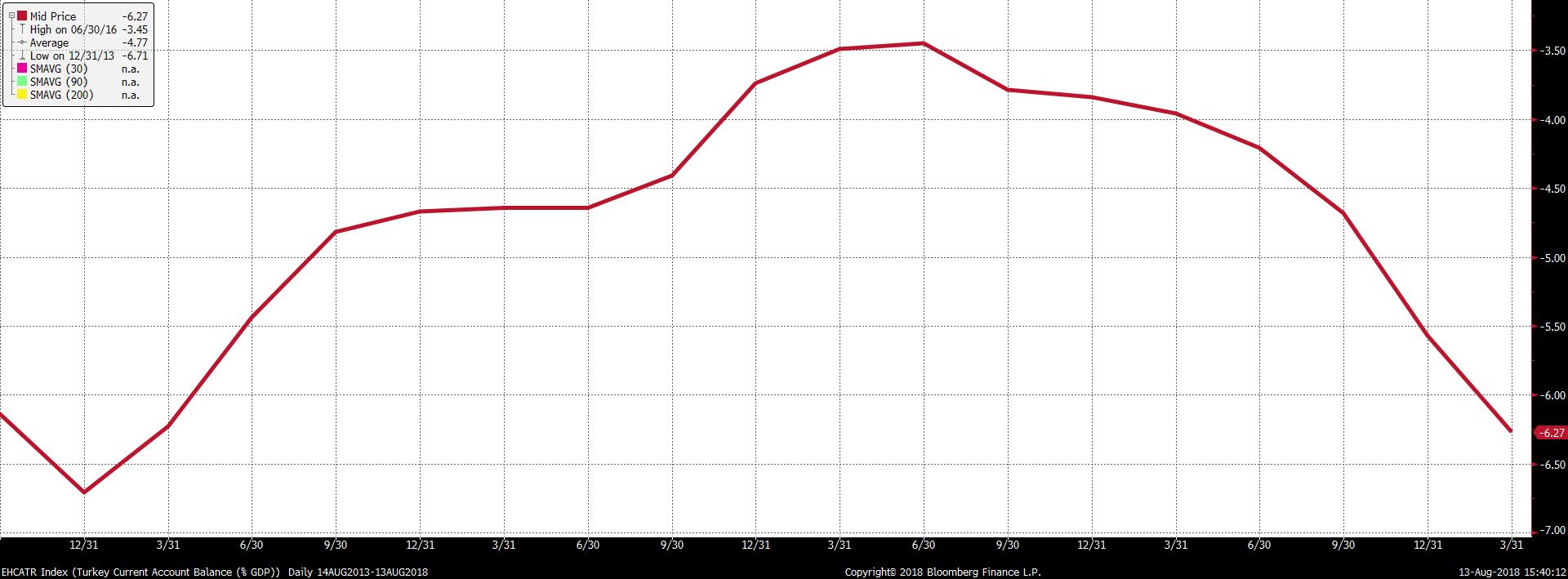

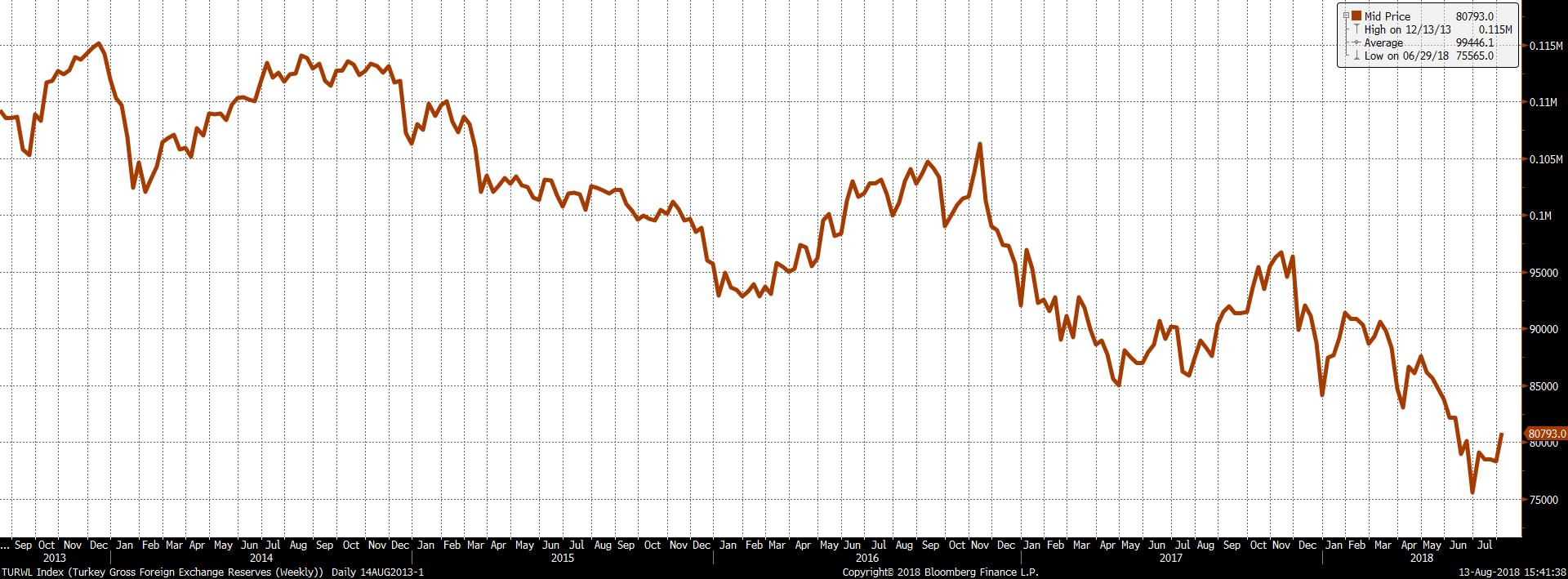

As money flows out of the country, its current account deficit is widening, to more than 6% of GDP (see first Chart below). This is forcing the central bank to sell down its reserves at a rapid rate (see second Chart).

Turkey Current Account Deficit as Percentage of GDP, 2013-2018

Turkey Gross Foreign Reserves, 2013-2018

Turkey has $466 billion of foreign debt, mostly (78%) denominated in US dollars, equivalent to more than half its GDP. About one-third of this debt is due within the year, and refinancing will be nearly impossible as bond investors have forced yields to more than 23% (see Chart below).

Yield of Turkey Government Bond 10.7% Due 02/2021, July-August 2018

The pattern of this economic crisis has been repeated hundreds of times, even as the details differ. Very low interest rates in the US and Europe in the wake of the 2008 global financial crash tempted Turkey to borrow excessively in foreign currencies. The money was used for uneconomic (i.e., politically-determined) projects that swelled the budget deficit. The excessive debt stimulated nominal growth, and loose monetary policy permitted inflation pressures to build unchecked. The markets responded by selling Turkish assets—stocks, bonds, the currency—exacerbating inflation and contracting the economy.

Years of economic mismanagement cannot be wished away, but the path to stability is well-documented: move the budget into a structural surplus, raise short-term rates above inflation, secure credit lines from the IMF or other creditors, accumulate foreign reserves. This will be painful—the economy will contract further, unemployment will soar, standards of living will decline—but it will bring stability from which recovery is possible. This won’t happen soon, and each day delay will only add to the inevitable pain and cost of salvaging a wrecked economy.

Sadly, Turkey seems to be following the well-worn path of so many failed states. Recip Tayyip Erdogan had been mayor of Istanbul in the late 1990s, and was elected prime minister in 2003. Initially, Turkey enjoyed strong economic growth and a vibrant democracy. But over time, Erdogan accumulated more power, and in 2014 he was able to amend the constitution to have himself named president. As power coalesced in one person, the institutions that define and defend a democracy—especially a free press—were eroded. In 2016, elements of the military, which had historically seen itself as defenders of democracy, staged a coup that was put down with much bloodshed. Subsequently, tens of thousands of military officers, teachers and civil servants lost their jobs under suspicion of supporting the coup. Since then, Erdogan has used the coup attempt as cover for gathering greater powers in the presidency and stifling political opposition. The markets believe, correctly, that there are no independent actors that can counterbalance the personal decisions of Erdogan. The new Treasury minister, Berat Albayrak, for example, is Erdogan’s son-in-law.

Turkey is a member of the NATO Alliance, and has been, for decades, a close ally of the United States. But relations deteriorated rapidly after the failed coup in 2016 when Erdogan accused Fethullah Gulen, a Muslim cleric living in Pennsylvania, of masterminding the coup attempt and demanded his extradition to Turkey. There is a formal extradition procedure that requires proof of likely complicity in a criminal act, but either that proof has not been offered or US officials found it unpersuasive. Regardless, Mr. Gulen remains in Pennsylvania.

In retaliation, or frustration, or both, Erdogan has detained numerous US citizens in Turkey and imprisoned Turkish staff working at US diplomatic missions. Serkan Golge, a Turkish-American scientist working for NASA, was recently sentenced to more than seven years in prison, and Andrew Brunson, an American evangelist living in Turkey for 20 years, is under house arrest, his release tied specifically to the extradition of Gulen. Erdogan sees these detainees are bargaining chips to mold US behavior in withholding support from Kurds fighting in Syria, and to scrap the fines imposed on the state-owned Halkbank for violating US-Iran sanctions.

Likewise, the US has demanded the release of Pastor Brunson, has clashed with Turkey over policy in Syria, and is worried by Turkey’s growing ties to Russia. Turkey, a NATO ally, announced it intends to buy the Russian S-400 missile defense system. The US will withhold the transfer of F-35 fighters to Turkey if it installs the Russian missile defense system. A few days ago, President Trump doubled the tariffs on Turkey’s steel and aluminum, to 50% and 20%, respectively. In reinstating sanctions against Iran, the US will block any country doing business there from doing business in the United States. Turkey imports most of its energy from Iran, and has few other energy options, as Iraq and Saudi Arabia are unlikely to assist a country that has become adversarial in the region. The US could block loans from the international credit agencies, and remove Turkish banks from the SWIFT money transfer system, which would likely bring financial collapse. This fight can easily escalate further.

Turkey is a minor actor in the world economy, with a GDP smaller than Los Angeles. There are a handful of banks, mostly Spanish, with relatively large loan exposure to the country, but a debt default should be able to be contained without systemic consequences. So for the world economy, the immediate consequences of Turkey’s crisis may not be all that material. But that doesn’t mean there won’t be other consequences of great importance.

A Turkish withdrawal from NATO would be a terrible blow to the Alliance, immediately and permanently. The complex and tenuous balance of relationships in the Middle East would be shattered, and a broader war more likely. Of course, the Turkish people will suffer greatly.

The erosion of democratic institutions allowed the concentration of power in a charismatic leader, which he used to further undermine democratic opposition to his rule and to antagonize former allies, thus threatening more instability for a region already in turmoil. It didn’t, and doesn’t, have to be this way.

Erdogan should release his American hostages (which is what they are), and accept the conditions imposed by the IMF for an economic bailout. Each day delay means even greater pain for the Turkish people. Unfortunately, this path is unlikely to be followed, and the consequences for the region and even the NATO Alliance, could be severe. I’m not talkin’ pretty, but I am talkin’ turkey.