Earthrise or Earthset: Thoughts on a Post-Pandemic World (Part 3)

Source: NASA

Weak economic growth and low investment returns are the prospects we discussed in the first two parts of this series (https://www.angelesinvestments.com/institutional-insights/sunrise-or-sunset-thoughts-on-a-post-pandemic-world-part-1; https://www.angelesinvestments.com/institutional-insights/sunrise-or-sunset-thoughts-on-a-post-pandemic-world-part-2). As important as the economic effects of this crisis will be, of much greater consequence will be the impact on our political system and in our societal structure. We are witnessing some of those consequences currently.

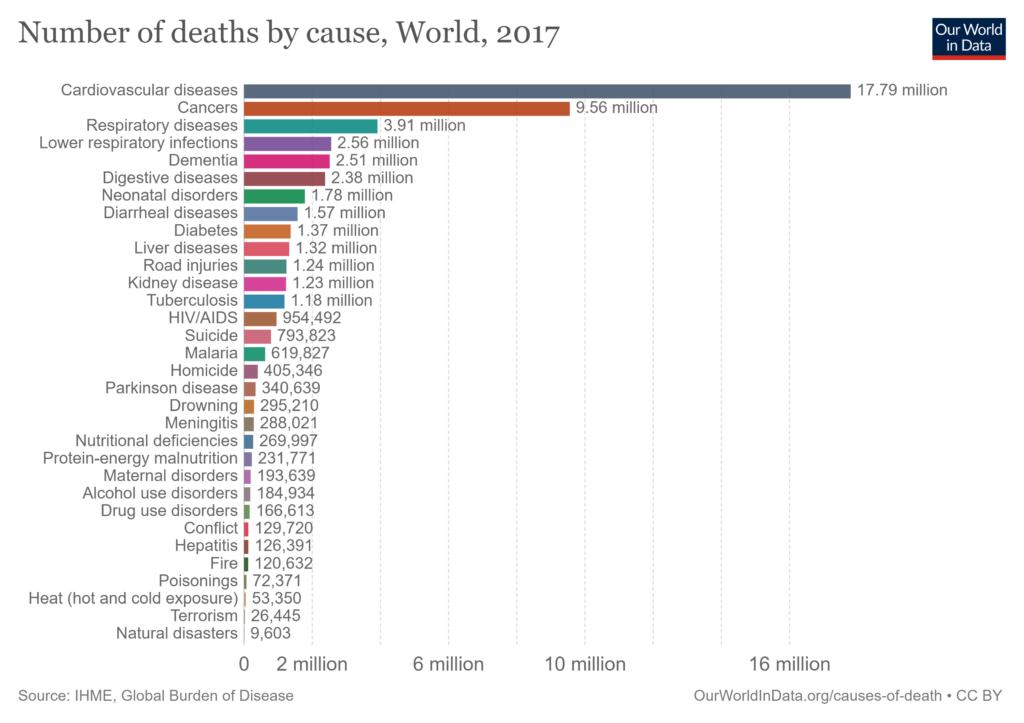

On one level, this global pandemic has been an insignificant health crisis. There have been approximately 400,000 deaths worldwide, fewer than in a typical flu season. Admittedly, the toll is still climbing, but it is unlikely to reach the more than a million who die each year from tuberculosis or traffic accidents, and much less than the ten million killed by cancer, or the nearly twenty million from cardiovascular disease (see chart below).

Even in economic terms, while the drop in output this quarter (expected to be off 40% on an annualized basis) and the rise in unemployment (to over 20%) are unprecedented, a sharp rebound is projected by the end of the year and into next. The US equity market has risen 36% off its March low in anticipation of a recovery. So, yes, the economic damage has been substantial, but likely transitory (although we outlined in Part 1 why we expect to see a sluggish pace of growth for years to come).

And yet. As I noted at the beginning of this series, something about this pandemic feels different—more significant, more fundamental—than past crises. It has accelerated shifts already underway, most clearly in our social and economic dependence on technology, exposed fractures in our society (more on this in a moment), and triggered behavioral shifts that may persist for a generation or more.

This behavioral change will manifest more clearly in certain parts of the economy. For example, in leisure and hospitality, travel and tourism, activity has fallen 90% or more. Humans enjoy socializing, we enjoy traveling, but we are now much more aware of the associated health risks, especially for those who may be more vulnerable. This awareness will make consumers more hesitant.

Public safety measures will be imposed, probably permanently. Health certifications may be required to enter buildings or public transit, as we see in some Asian cities now. Those with elevated risk may be denied entry or even prohibited from free movement in the name of protecting public health. Constitutional liberties will have to contend with public health priorities. Privacy concerns will be raised about access to personal health data. These are contentious issues, and how we resolve them will determine the kind of society we wish to have.

I commented in the introduction to this series that the pandemic has exposed profound vulnerabilities in our society. We can see these as economic issues, but their impact is as much (or more) political, for it is an expression of the nature of our society. Let me highlight two such areas of glaring inequity: health care and inequality.

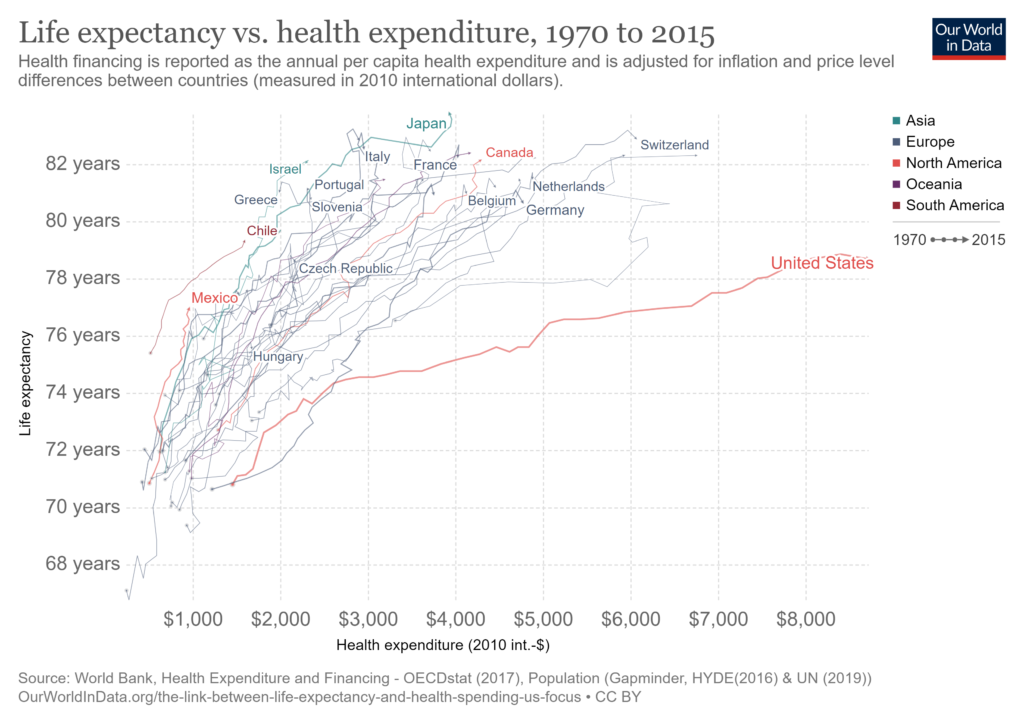

Our health care system is an abomination. Not only do 28 million Americans have no health insurance, we spend far more on health care than anywhere on earth. This might be acceptable if our health outcomes were the best, but sadly, that is not the case. The United States spends more than $3 trillion annually on health care, two-to-three times more per capita than in other advanced economies. Life expectancy, one measure of health outcomes, is, however, well below that of Western Europe and Japan. We pay much more and get much less (see chart below).

These facts were true before the pandemic, but it took the concrete examples of abject failure—the unconscionable lack of testing kits, protective equipment, basic drugs, and the consequential needless deaths—to reveal the failure of the system. This is not a condemnation of the many heroic health care workers who have risked their lives to protect the public, but of an entire economic and political structure that failed on many levels to protect the health and safety of its citizens. This is the most fundamental (some might say only) requirement of government, and it fell miserably short.

This is not an advocacy for a single payer system, such as in the United Kingdom or in Cuba. Some countries have mandatory insurance requirements, such as most of Western Europe and Japan, others have a national health insurance program, such as Canada and South Korea. My own non-expertise, and space in this letter, do not permit a full debate on the optimal structure of our health care system. But surely we can agree that an insurance scheme tied to employment through massive tax breaks, a structure that leaves tens of millions uninsured yet still required to be provided for in an emergency, a system that costs far more than any in the world with outcomes that trail most other countries, needs fundamental change.

The averages, as abysmal as they are, mask important failures, namely that there is a widening gap in health outcomes for the wealthy and for the poor. Life expectancy has fallen for the bottom income quartile as it has risen for the top income quartile. This is indicative of a larger growing wealth and income gap, a gap that is as indefensible on moral grounds as it is untenable in economic and political terms.

Since 1980, real GDP per capita in the United States rose 79%, but for the bottom 50% of the population, after-tax income has risen just 20%. For the next 40%, income was up only 50%. For the top 0.01%, however, income rose 420% in this period. According to research by Raj Chetty and his colleagues, those born in 1940 had a 92% chance of earning more than their parents, but it is a coin-flip (50%) for those born in 1980 (Chetty, Raj, David Grusky, Maximilian Hell, Nathaniel Hendren, Robert Manduca and Jimmy Narang, “The Fading American Dream: Trends in Absolute Income Mobility Since 1940,” March 2017). The richest 0.1% of Americans own 19.6% of the nation’s wealth, up from 7.4% in 1980. The top one-tenth of 1% own the equivalent of the combined net worth of the bottom 85%.

The pandemic has exacerbated these trends. In April, one-in-five workers were either laid-off or on furlough, but for those earning less than $40,000 per year, 40%, twice as many as the national average, were without a job. Many of those are jobs that will be slow to return, if ever.

Wealth and income inequality have been rising for many years, not only in the United States but in most advanced economies. But the pandemic has accelerated this chasm, and we all must acknowledge that the trend is unacceptable on moral grounds and unsustainable in political terms. The pandemic has brought greater urgency to addressing inequality.

There is one additional threat that this pandemic has brought into greater clarity (literally and figuratively) and that requires our urgent attention: the environment. There are important similarities between the pandemic and the looming climate catastrophe (which is already here), and both challenges require a similar approach.

A recent McKinsey study (Pinner, Dickon, Matt Rogers and Hamid Samandari, Addressing Climate Change in a Post-Pandemic World, April 2020) drew a number of parallels between pandemics and climate change. Both are systemic, with worldwide effects. Both are non-stationary, with past probabilities unlikely to be a sufficient guide to make future projections. Both are nonlinear, with impacts that expand catastrophically beyond certain thresholds. And both are regressive, hurting the poor disproportionately.

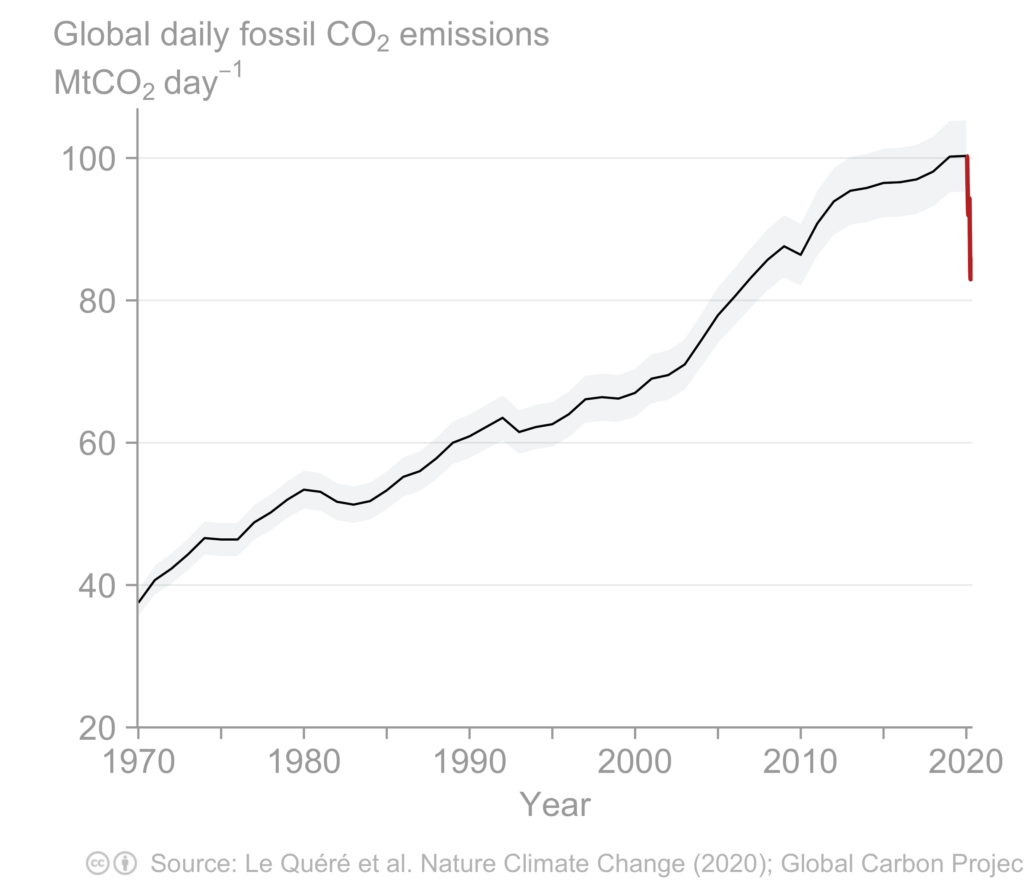

We witnessed an extraordinary experiment by shuttering much of the global economy these past few months: material declines in carbon emissions. In April, daily carbon emissions fell, on average, 17% below levels from the year before (see graph below). As desirable as this is, we know we cannot cut emissions by closing the world economy permanently.

Global Daily CO2 Emissions

An important difference between pandemics and climate risk is the time scale. Pandemics represent immediate dangers whereas climate change poses a cumulative threat. We accepted harsh restrictions on our activity because we saw the pandemic threat as immediate (as it was/is). But so far, we have not been willing to accept any sacrifice to avert environmental catastrophe because it is on a different time scale. This is massively myopic, and recalls Hemingway’s dialogue in The Sun Also Rises: “How do you go bankrupt? Two ways. Gradually, then suddenly.” That is our fate if we continue to heat the planet.

The most important trait shared by pandemics and environmental risk is that they both represent the “tragedy of the commons,” a concept first articulated by Oxford economist William Forster Lloyd in 1833. He observed that each shepherd personally benefited from adding more cattle to graze on public land, which then caused the pasture to be overgrazed, thereby providing less food for everyone’s cattle. Lloyd identified that the gain of having more cattle would accrue to the individual, whereas the loss to the commons would be shared by all. Individual gain was incentivized at the expense of the common good, and this was the “tragedy.”

Global pandemics and environmental dangers also represent a tragedy of the commons. Behavior that may be profitable for an individual, traveling while asymptomatic or polluting, for example, incur costs, potentially catastrophic, that are borne by all. Historically, the tragedy of the commons has been addressed by imposing rules (limits) on everyone. Overfishing, which brought the once-limitless supplies of cod in the Grand Banks, for example, to near-extinction, led to international fishing restrictions that are permitting the natural re-stocking of the species.

Viruses and CO2 do not respect political boundaries. Global pandemics and environmental crises cannot be combated by individual countries, but only through global coordination and cooperation.

Perhaps that is the greatest tragedy of this pandemic. We (China and the US, in particular) have chosen to obfuscate, deny and attack (both their domestic critics and each other) for illusory political advantage rather than to share resources and best practices which would have contained this disaster. As we failed to coordinate to combat the pandemic, and we have missed an opportunity to cooperate on the environment. We could have imposed a carbon tax with oil prices low to invest in renewables, but we did not. Our political leaders chose to provide fiscal support to oil and gas companies, but not to renewable energy. We are jeopardizing life gradually, and then it will be suddenly.

The COVID-19 virus will be contained. Others will inevitably arise. Global warming is a threat that has been given a very short reprieve as we closed the world economy, but it is back in force as a global danger as we resume our activity.

Our most urgent challenges require collective action, across communities and throughout the globe. A failed health care system, an abhorrent disparity in wealth, future pandemics and environmental disasters all demand our attention and resources. But mostly, they require our will.